Visit the state capital Erfurt and go on a virtual discovery tour through Thuringia.

The remarkable glassblowers’ wives

Or why the success of Christmas tree ornaments is mostly down to women

Glass Christmas tree ornaments were first produced commercially in Lauscha in 1848, and the tradition survives in family-run businesses along the Rennsteig Trail to this day. Elfi Bartholmes inspects her work. She deftly creates lines, patterns or even entire landscapes with houses on the delicate, featherlight globes. Most of the design templates she follows are more than a hundred years old. As a final touch, she carefully sprinkles some glitter over the glass sphere – that’s another sparkling Christmas bauble finished!

The techniques and the entire manufacturing process have remained essentially the same to this day, and so has the distribution of roles. The men sit at the gas burners and blow the glass shapes for the ornaments, while the women paint and decorate the fragile glassware. The glassblowers’ wives play a key role in the process, just as they did originally when they helped make the first Christmas tree ornaments from Lauscha a leading export around the world.

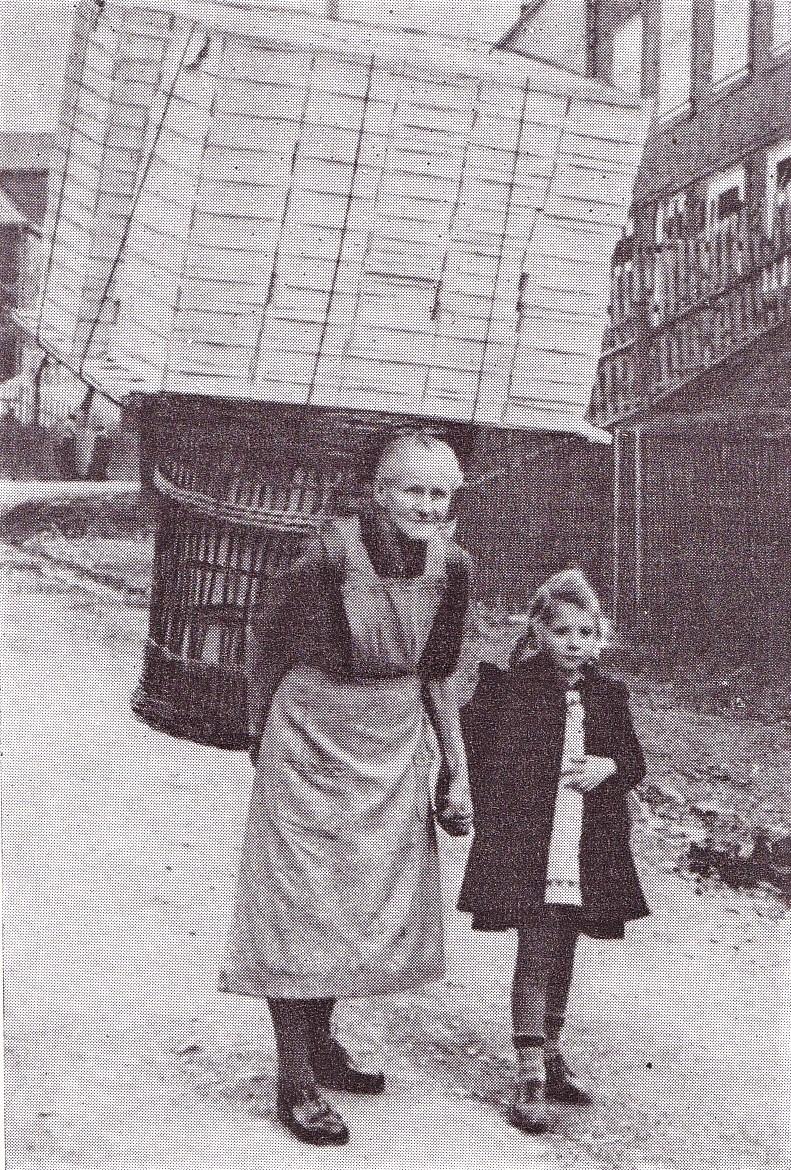

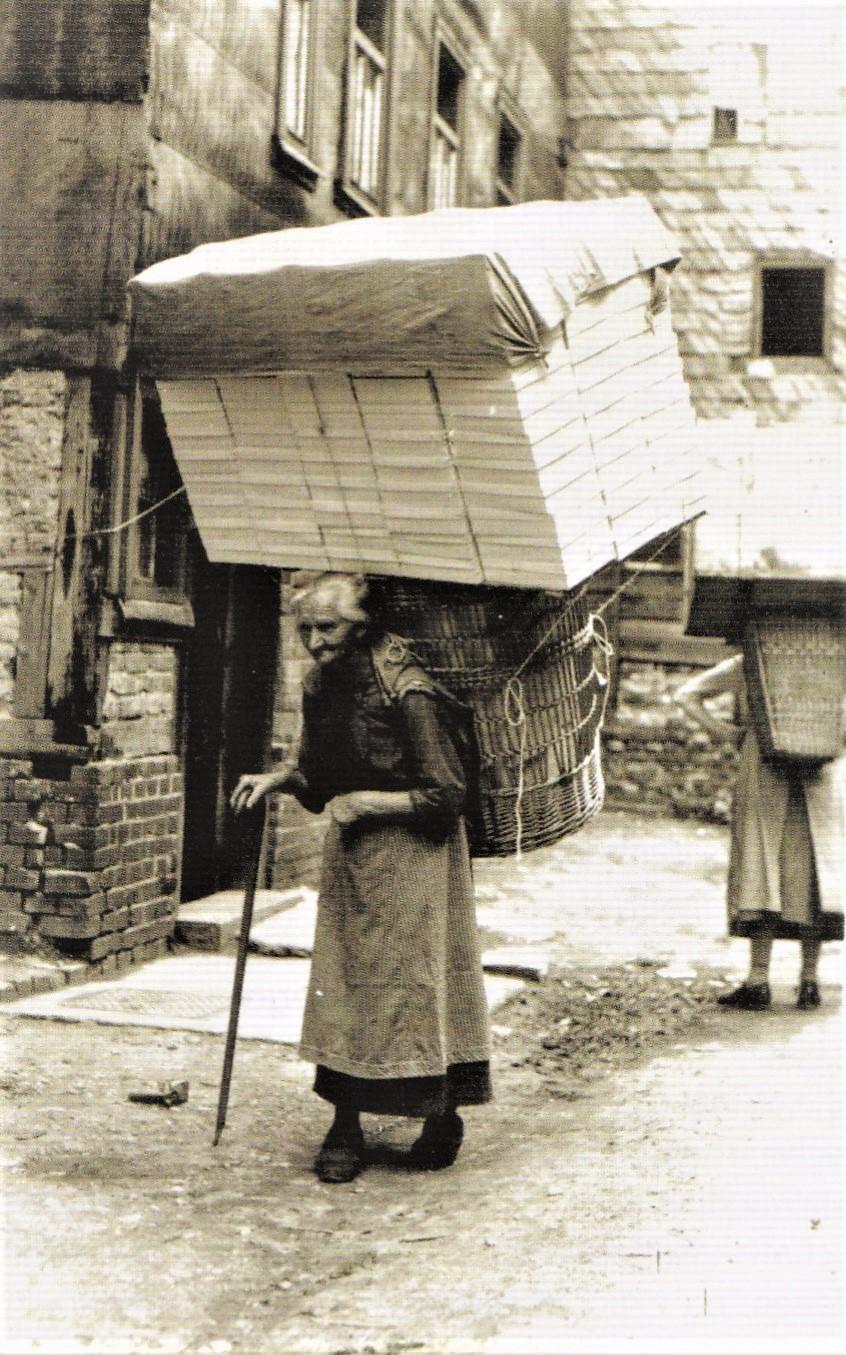

Until the 20th century, Thuringian Christmas tree ornaments were produced according to seasonal demand. In the spring and summer months, the glassblowers’ wives took samples of the new designs to the merchants, who had their offices and warehouses in the toymaking town of Sonneberg. From there, the glass Christmas tree ornaments were distributed around the world. The merchants placed their orders, and during the autumn – winter tends to come early in Lauscha – the women had to travel most weeks to deliver the finished goods. The road known as the ‘glassblowers’ path’ runs for 15 kilometres through deeply carved, narrow valleys – right through the coniferous forest of the Thuringian Slate Mountains – from Lauscha to Steinach and on to Sonneberg. One particularly gruelling ascent beyond Steinach is known as ‘hell’, which gives some indication of the huge efforts the women were making. On their own, in all weathers, and all the while transporting large packs that weighed up to 30kg on their backs across the Thuringian mountains. If a load got broken it meant a family lost a whole week’s work. Before setting out on their long return journey, the women used their meagre pay to buy paint and decorating materials. Women carrying huge willow baskets were a common sight in the streets of Lauscha in those days.

Historical photo from Lauscha, 1930. The glassblowers’ wives carried Christmas tree ornaments for 15 kilometres to Sonneberg in willow baskets. The baskets generally weighed more than 20kg and the road was very difficult, particularly during the winter months. ©Museum of Glass Art Lauscha

Later on, the glassblower families also employed delivery women to take their goods to Sonneberg. They usually collected several glassblowers’ baskets at Lauscha train station and looked after the cargo until it reached Sonneberg.

But some of the glassblowers’ wives and the delivery women continued to walk to Sonneberg right up until the 1950s. Their particular way of life, constantly on the road, travelling long distances, turned some into well-known personalities – in a few cases they even became true local legends. Louise Petzold, better known as Korz (Shorty), worked up to the beginning of the Second World War. Emilie Hellmann, the delivery woman covering Inselsberg mountain, was still scaling its heights on her 70th birthday. She climbed the mountain 12,000 times, which is the equivalent of walking around the equator two and a half times.

Historical photo from Lauscha, 1935. Some of the glassblowers’ wives became legendary for making the trip until well into old age. ©Museum of Glass Art Lauscha

Today, the historical road from Lauscha to Sonneberg is a popular walking trail. The unsurfaced path covers an altitude difference of around 400 metres and give walkers a hint of the struggles and hardships the women had to endure. But at the same time, you can see that the region is preserving its heritage. The craft of glassblowing remains very much alive in the small villages along the Rennsteig Trail. It is the family businesses – like the Thüringer Weihnacht glassblowing workshop – that are upholding this local legacy. Elfi Bartholmes inspects her finished piece with justified pride. She doesn’t have to make the arduous journey to Sonneberg – unless it’s for leisure, suitably equipped with walking gear and a hearty picnic. But she is well aware that it was only thanks to the delivery women that Christmas baubles from Lauscha were able to take the world by storm.

Traditional Christmas tree ornaments from the Thüringer Weihnacht glassblowing workshop. Most of their moulds and designs are well over 100 years old. ©Florian Trykowski, Thüringer Tourismus GmbH

FILM "THE GLASSBLOWER"

Header picture: ©Museum für Glaskunst Lauscha

Did you like this story?

Maybe, you'll like this too ...