Visit the state capital Erfurt and go on a virtual discovery tour through Thuringia.

The Bauhaus didn’t come out of nowhere!

A conversation with curator Sabine Walter of the Museum Neues Weimar.

You’ve said in an interview that Modernism around 1900 was a mission – what exactly did you mean by that, and what is the mission of this permanent exhibition?

Many artists around 1900, including Henry van de Velde, saw Modernism as a positive future that they actively wanted to be involved in shaping. They felt that the nationalistic fervour and ambiguous morality of their society were at odds with the innovations being achieved in the area of technology. The rigidity of the time is reflected in the homes of the period, which were stuffed full of trinkets and draped in heavy fabrics. Both architecture and interior design were focused on the past.

Nietzsche wrote that it was impossible to think new thoughts when surrounded by Renaissance, baroque and rococo. Many artists turned to decorative arts in order to usher in the dawning of the modernist era in everyday life. They were not just satisfied with painting new pictures, but wanted to shape the world around them through contemporary products. Many architects and designers saw it as their mission to create new forms for a new age.

The mission of the exhibition in our museum is to convey history through art, to help us understand why we are where we are today. And the visit should be fun, of course.

In the introduction, we mentioned three figures who paved the way for Modernism in Weimar – could you give us a brief overview of the individual characters and the roles they played?

We’re showcasing the Belgian art reformer Henry van de Velde who wanted to create new forms for new people. Having studied painting, he perceived the world around him as ugly and taught himself product design. Only ‘rational’, i.e. plain, functional design met his standard for ‘beauty’. He described his approach to design in articles and lectures, and he taught it at the School of Arts and Crafts in Weimar, which he had established.

Van de Velde was said to be of small stature with an agile mind and great charisma. His wealthy clients believed in his mission. The interiors he designed for them allowed them to portray themselves as modern, open-minded and stylish. Van de Velde’s own life was quite unconventional by the standards of his time. His wife Maria, a strong, independent woman, designed reform clothes, served at table herself – a task strictly reserved for servants in polite society – and enjoyed gardening. Their five unbaptised children were deemed to exhibit behavioural problems, presumably because they hadn’t been brought up to conform to rigorous Prussian manners. The former residence of Henry van de Velde and his family – Haus Hohe Pappeln in Weimar – in Weimar – is definitely worth a visit.

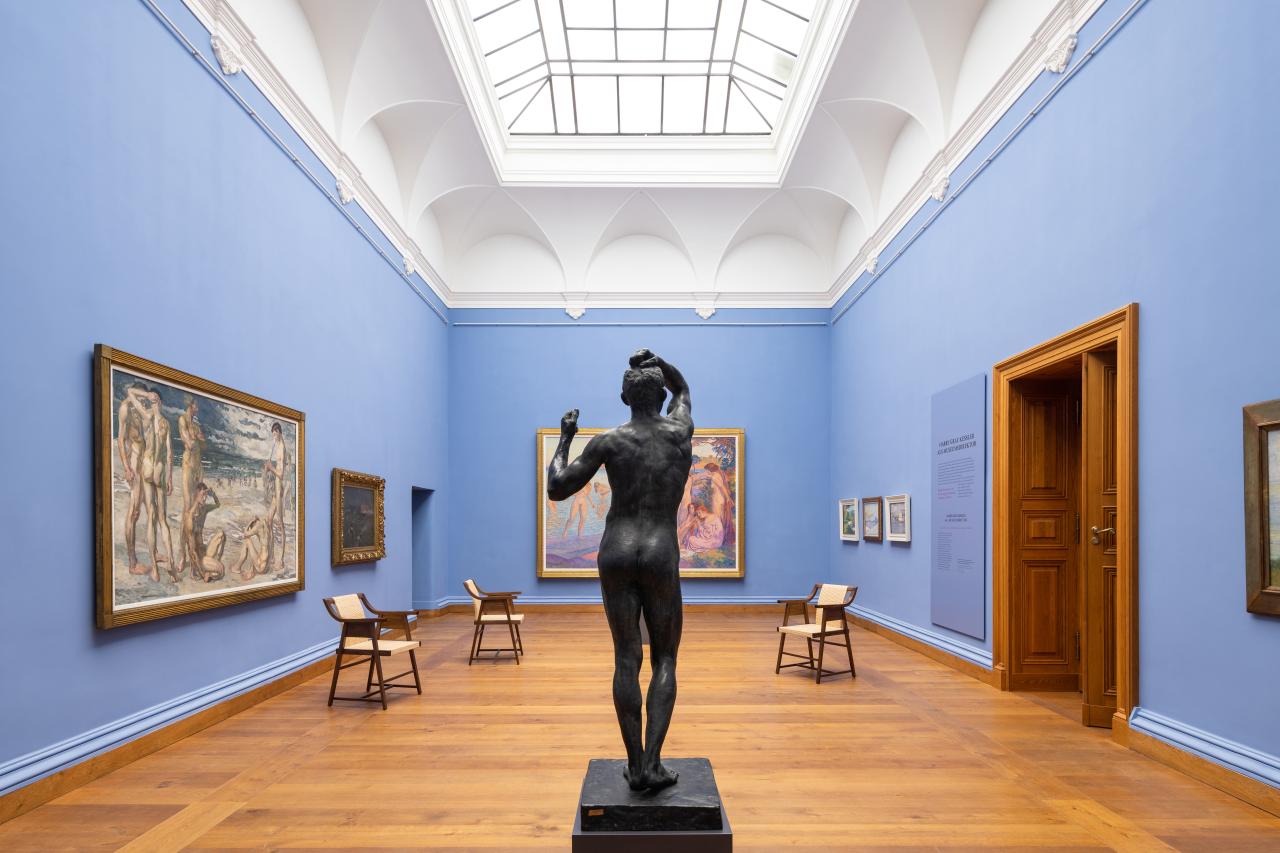

The exhibition also features Count Harry Kessler. Being independently wealthy, Kessler did not need to earn a living, but still desired to establish a useful role for himself in society, which he found as a patron of European avant-garde art. A dedicated follower of Nietzsche, he believed in the responsibility of the elites, in Europe, and in Modernism, of course. In his role as unpaid museum director he scandalised Weimar society by exhibiting progressive artwork and craft objects, primarily from France, Belgium and England. The new techniques, forms and subjects caused outrage, as did the number of ‘foreign’ items. Kessler had to rely on private funding to enable him to acquire works by Rodin and Monet for the museum.

The ‘Harry Graf Kessler exhibitions in Weimar’ room. A skylit room with impressionist and neo-impressionist works acquired by Count Harry Kessler for the Weimar Museum. ©Thomas Müller, Klassik Stiftung Weimar

Count Harry Kessler was immensely elegant, extremely well educated and fluent in three languages. Dina Vierny, muse to the sculptor Aristide Maillol, remembered him as a slender man with a high voice. He moved in aristocratic and artistic circles across Europe. Nowadays we might describe him as a networker or perhaps an influencer.

The museum is also dedicated to a third important figure from the period of change that marked the turn of the 19th century, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, sister of the great philosopher. She recognised her brother’s potential and founded the Nietzsche-Archiv which provided a focus for the cult that was beginning to form around him. With the help of Count Harry Kessler and other supporters, Elisabeth transformed her own house in Weimar into a temple to the Nietzsche cult. Henry van de Velde designed the interior, creating an aesthetic work of art.

Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche was a shrewd marketing strategist who deliberately played up her perceived weakness as an uneducated widow to win over benefactors. She seemed like a harmless elderly lady, with her lace cap and lorgnette spectacles, but all the while she was eliminating her critics using defamation as well as legal means. She went on to shape the perception of Nietzsche and his work for decades to come.

‘Nietzsche cult’ room. The Preller Gallery with portraits of Friedrich Nietzsche, including two famous busts created by Max Klinger. ©Thomas Müller, Klassik Stiftung Weimar

This was generally a time of reform – the dawning of a new era in society. What still remains of that today, what survives as the legacy of Modernism?

In many respects we are very much heirs to the changes at the turn of the 19th century. Today’s enthusiasm for outdoor exercise, plenty of light, fresh air, nature and vegetarianism, and our healthier approach to how we dress, to say nothing of the emancipation of women, are all ideas that date from this period. At the same time, we are still wrestling with the same contradictions. Designers back then also demanded ‘fair’ production, by which they meant paying reasonable wages to craftspeople and insisting on high-quality materials to ensure that products would last. But this led to high prices, which only the well-off could afford. The modern style was meant to change society. However, innovative, fairly produced and high-quality products are still expensive. That conflict has not yet been resolved.

You curated the exhibition together as a team – what are you particularly proud of?

I’m pleased that we were able to design the exhibition to be quite a sensory experience. One way we achieved that was by using strong colours for the walls. They highlight the beauty of the objects. When it came to choosing the colours, we took our inspiration from Henry van de Velde, who used very unusual hues for wallpaper and textiles. The room devoted to the Weimar School is done in a light grey, which reflects the mood of the paintings. The dark green of the room that contains furniture from Wartburg Castle corresponds exactly to samples from the room where the items were located in the 19th century.

But the real sensory appeal of the exhibition comes from the many opportunities for hands-on involvement. The exhibition is an interactive experience for the whole family. For example, you can explore the difference between academy-style fine art painting and the newer pastose technique by touching sample paintings. A Q&A game tests how well you know to behave in polite society, allowing you to see how ‘cultured’ you really are. The knowledge and application of art and style were used above all to indicate social status. And finally, everyone can join together to battle against backward-looking intransigence and literally knock historicist elements off a functional ‘modernist’ piece of furniture.

We had great working relationships with everyone. Among the curatorial team, we were able to think outside the box and explore some blue-sky options. Many people have told me that it’s clear from the exhibition how much fun we had putting it together.

The exhibition opened in 2019, to coincide with the ‘100 years of Bauhaus’ celebrations, and the Bauhaus Museum Weimar is very close by. Was it a challenge to differentiate the content, and what are the main differences?

Differentiating the content was easy, because the museums complement each other. At the Museum Neues Weimar we are showing early Modernism, with a focus on paintings by the Weimar School, as well as Impressionism and art nouveau by Henry van de Velde and his school, of course. The Bauhaus doesn’t enter the frame until the 20th century. The exhibition at the Bauhaus-Museum Weimar is based around Walter Gropius’ 1924 question: “How do we want to live?”

To put it another way, you could say that the Bauhaus didn’t come out of nowhere! For anyone keen to explore the history of its origins, our permanent exhibition at the Museum Neues Weimar provides an ideal foundation.

Museum Neues Weimar. The former grand ducal museum, one of Germany’s first purpose-built museums, opened in 1869. Having most recently been used to house temporary exhibitions, it reopened as the Museum Neues Weimar in April 2019. Its permanent exhibition showcases the art of early Modernism from the Weimar School to Henry van de Velde. ©Jens Hauspurg, Klassik Stiftung Weimar

Surely the highest praise for you is feedback from your visitors. Does anything in particular spring to mind in this regard?

I was deeply impressed by the response from a class of primary school children. Shortly after the exhibition opened, the children wrote to me to point out a mistake on one of the labels. Sure enough, there was a panel with a long list of individual pieces of cutlery by Henry van de Velde where I had missed out an object, a small mocca spoon or something like that. I was amazed at the extent to which the children had engaged with the details.

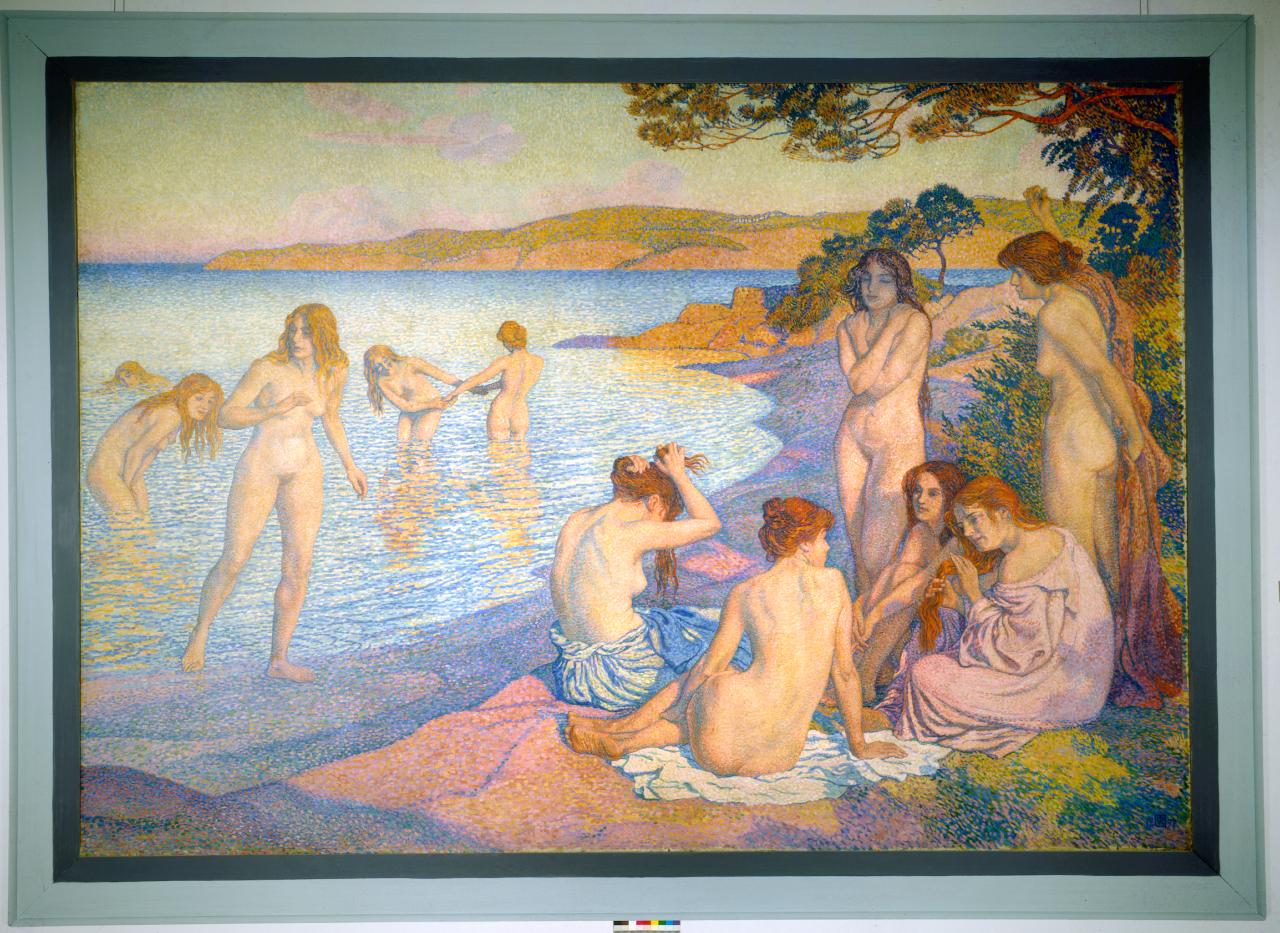

On a guided tour for teenagers, the body hair of the female nudes in a neo-impressionist painting by Théo van Rysselberghe got mentioned amid much sniggering. And it is indeed unusual, as throughout art history nudes have tended not to feature body hair. But the painter is trying to depict an authentic, non-academy style nudity, the outdoor exercise in natural surroundings I mentioned before. Those young people recognised that there was something about those nudes, and they were brave enough to raise what was potentially an embarrassing subject – good for them!

Guided tours for visitors from France or the US can also be a bit of a revelation. As soon as they enter the building, they realise that the staircase was designed by Daniel Buren. The French conceptual artist is not particularly well known in Germany.

Artist: Théo van Rysselberghe’s ‘Bathing Women’ (L’ Heure embrasée, Het blakende uur), dated: 1897. ©Renno, Klassik Stiftung Weimar, Bestand Museen

And finally we’d like to ask you for three tips and/or three of your personal favourites:

- What are your three favourite exhibits and why?

I love our replicas. We’ve got some reproductions of famous chairs that visitors can use. It’s great fun to be able to sit in a Vollmer armchair and look at the artworks in the room, just like in Kessler’s day. - The Bloemenwerf chair by Henry van de Velde is an iconic piece of art nouveau. I love this exhibit, because it seems rather awkward and ascetic in comparison to his later, more elegant works, although it does contain a basic notion of functional design within its almost architectural structure reminiscent of the Eiffel Tower.

- The third of my favourites is an entire room, the Blue Room, which contains our Impressionists and Neo-impressionists, and is a delight for all the senses, according to the press.

What else should visitors to Thuringia be sure to see? Give us three recommendations.

- The Nietzsche Archive with its new permanent exhibition and detailed restorations is well worth a visit. It explains Nietzsche in a simple, accessible way, and the rooms themselves are absolute treasures of the art nouveau style.

- Haus Hohe Pappeln, where the van de Velde family lived, is a definite must-see. Although it was designed according to an overarching aesthetic theme, it is still a family home. The complete ensemble includes the garden, which is particularly impressive in spring.

- I can also recommend Haus Schulenburg in Gera, a veritable palace compared to the Nietzsche Archive or Haus Hohe Pappeln. This privately run museum contains many fascinating exhibits.

Headermotiv: Museum Neues Weimar ©Thomas Müller, Klassik Stiftung Weimar

Accessibility

Did you like this story?

You might also be interested in ...